Tags

This post is part of the derivative works genre post series, this month’s selection for Movie Rob’s genre grandeur, and this theme, derivative works, was selected by yours truly. Now, what is a derivative work? We hear this phrase bandied about in fan studies, often to describe fan fiction.

For this event, we define it as work based on existing source material but reinvents the material into something special, which is a wide selection, because almost everything is adapted from something nowadays.

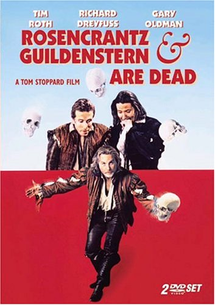

But when I think of derivative works, Tom Stoppard’s 1990 film Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead comes to mind as the grandaddy of all reinventions.

But when I think of derivative works, Tom Stoppard’s 1990 film Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead comes to mind as the grandaddy of all reinventions.

Based on Hamlet, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead follows the play’s ancillary characters, as they move amongst the larger actions of the Danish court.

Normal people have the nightmare about being in highschool and taking a test for which you are unprepared. That is easy.

Now, imagine you find yourself in a play with no recollection of how you got there, that’s the typical actor’s nightmare. I have that one all the time.

Now imagine that play is Hamlet.

Now imagine instead of being on stage which is bad enough, this play is actually happening to you, and you know absolutely nothing at all, all you know is that someone sent for you.

That is the premise for Tom Stoppard’s play and 1990 film adaptation of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead.

If you recall your Shakespeare, you know that Rosencrantz (Gary Oldman) and Guildenstern (Tim Roth) are Hamlet’s childhood friends, who are summoned to Elsinore to “glean what afflicts” Hamlet in his madness.

The problem is the characters in this film have no knowledge beyond what Shakespeare has written for them, which is very little, we know they were sent for, they are incredibly witty and somewhat interchangeable, they travel with Hamlet via boat to England, and at the end of the play the English ambassador announces they are dead (you can’t call it a spoiler when it’s in the title).

Spoilers! No, not really.

But how they get to that point is what makes this film a masterpiece.

Heads.

Heads.

Heads.

A coin repeatedly flips and lands on Heads, again and again, 168 times in a row to be exact. Rosencrantz is delighted with his unbelievable luck; Guildenstern is alarmed. What follows is an existential crisis.

Our two central characters are traveling in a gray landscape with no sense of time or place; they cannot remember anything, beyond the fact that they were sent for. Imagine finding yourself on a journey, knowing your name only because someone shouted it at you, and not knowing where you are going.

They shortly joined by The Player (Richard Dreyfus) and a troupe of actors; The Player sets up for the audience what we are watching, “We do on stage the things that are supposed to happen off.”

And that perhaps is the best way to describe the film, the action of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead is what happens during Hamlet to Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. So the characters in the film are performing what is going on in the play when the characters in the play are off stage. Sometimes they will perform and interact with the characters on stage, but they are not on stage, and the characters who perform the play within the play are the only ones who know they are in the play or waiting to be in the play, everyone else considers it their reality. How meta can you get? Stick with me, this film is great!

Another toss of the coin, it lands on tails, and suddenly we are whisked to the royal court in the castle at Elsinore in Denmark.

The metaphor of the coin repeats throughout the film, and can be interpreted in several ways. Firstly the coin flipped in repetition suggests our characters are limbo, not existing until they are “on stage” or in the world of Hamlet. It is only when the coin lands on tails that the action begins. The coin returns as a literal currency; the performers will perform for even a single coin, and as a metaphor for patronage and performance, for you cannot perform without an audience. The toss of the coin also represents chance, as Guildenstern later reflects, “there must have been a moment when we could have said no.” The moment before the coin landed on tails.

Back to Elsinore, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern find themselves speaking lines that aren’t their own to people they have never met, and as quickly as the court arrives, they vanish, and again our two characters are left to contemplate their strange existence.

Hamlet (Iain Glen) in full Olivier madness joins our friends for a bizarre conversation

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead marked by long periods of no action, eavesdropping, waiting in the wings. The wait is not tedious, both Oldman and Roth are fantastic actors. While Rosencrantz appears dim-witted, his character has moments of genius, recreating Galileo and Newton’s experiments with gravity, inventing the steam power, feats of aviation, and the Big Mac.

While these bits seem anachronistic, they work within the world of the film. The opening credits are underscored with a deep southern slow blues and howling hounds, as the spectator, we know we won’t see Shakespeare, to quote the film, “audiences know what to expect, and that is all they are prepared to believe in.” Guildenstern is a well-schooled philosopher relying on logic and reason, he questions everything in respect to his existence and is extremely frustrated by being stuck with Rosencrantz with whom he can only hold a comic conversation.

While these bits seem anachronistic, they work within the world of the film. The opening credits are underscored with a deep southern slow blues and howling hounds, as the spectator, we know we won’t see Shakespeare, to quote the film, “audiences know what to expect, and that is all they are prepared to believe in.” Guildenstern is a well-schooled philosopher relying on logic and reason, he questions everything in respect to his existence and is extremely frustrated by being stuck with Rosencrantz with whom he can only hold a comic conversation.

They are even unsure who is Rosencrantz and who is Guildenstern, as they play games of questions, and logic, they are “presented with alternatives, but not choices.”

What makes this film truly brilliant, is how close it stays to its source material, Hamlet. Stoppard manages to create a believable world within the world of Hamlet, the characters Rosencrantz and Guildenstern deal with Hamlet’s infamous question “To be, or not to be” with an almost equally famous monologue:

As both characters question their existence regarding destiny, free-will, they consider their own mortality, after all, they are moving towards their inevitable pre-determined death, “Events must play themselves to their aesthetic, moral, and logical conclusion. … We aim for the point where everyone who is marked for death dies.”

Shakespeare’s text is interwoven throughout the film, giving an audience a sense of the world where our two main characters exist, for they exist only within the world of the play, they were called for, they move through the story, and they die. Their death is not an exit, but an entrance somewhere else; we get the sense from The Player (Dreyfus) that he knows that this will be repeated again, for they are all merely actors.

Hamlet is a tragedy and a bloodbath with a total of eight corpses before the final curtain. It is the perfect classic tragedy, as we watch exalted characters fall from heights, a reversal of fortune to their eventual deaths. Their deaths are distant from our own. Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead is an absurdist comedy, giving the audience much to consider of our life spans and our own meaning. These characters represent the every man, though they are likely high-born being friends with the prince, they feel like everyday people, they are mere pawns on the chess board, with little control of the world around them.

Guildenstern: Who are we that our deaths should have so much meaning?

Player: You are Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, that is enough.

The film ends with the inevitable and expected deaths of our heroes, the tragedians pack the stage and move on.

The audience is not left with the finality of death, but the circular nature of existence, we know that these characters will live again when Hamlet is performed, and if where you live is anything like my area, we know that is quite a lot.

The stage version of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead is extremely popular in University towns, but the is film is rarely shown, there is a version streaming on youtube, you can watch it here.

Interestingly, this is not the only derivative work based on Hamlet, which uses Rosencrantz and Guildenstern in the title. W.S. Gilbert, of Gilbert and Sullivan, wrote a comic parody of Hamlet entitled Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. There is a 2009 film entitled Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Undead, which is about a Hamlet production starring vampires, don’t get excited, it is not nearly as grand as it sounds, and it has nothing to do with a Seth Grahame-Smith novel.

But what sets Stoppard’s film apart from the others, is that it reinvents the material and allows for something equally wonderful which exists in a parallel timeline, and if you can make an old chestnut like Hamlet feel fresh, you know the playwright must be doing something right!

Be sure to visit MovieRob and find out how my fellow bloggers tackled the derivative works! I am super excited to read everyone’s posts!

Ciao for now, dearies.

Today I leave you with the words of the immortal bard:

And all our yesterdays have lighted fools

The way to dusty death. Out, out, brief candle!

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage

And then is heard no more: it is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.Macbeth Act V, Sc 5

Summer

excellent review Summer! tnx!

LikeLike

Thanx for hosting, looking forward to enjoying everyone’s posts! 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

They’ll be up on thurs

LikeLiked by 1 person

fabulous, send me the link I will update my post to redirect the readers.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Heads!

I actually think this is a pretty tough movie to talk about but damn you did good here!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks! It is one of my all-time favorites 🙂

LikeLike

Love this movie, love this play, love this review!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Excellent taste, sir, it is one of my all-tike favorites too!

LikeLike

Way back when this was released we were all ‘forced’ to watch this for highschool English. Nobody enjoyed it, I think for that very reason. I remember very little about it, but I think if I was to revisit it now, I would have a better appreciation for it. Great review. 🙂

LikeLike

Love, LOVE this film. I think it’s my fave Richard Dreyfuss performance.

Coincidentally, I was thinking about this film the other day and how long it’s been since I’ve seen it. Thank you for embedding it in your post! I’ve bookmarked it to watch later.

I agree with a previous commenter who said this is a hard film to talk/write about, but I think you nailed it. Well done!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, It really is an underrated classic!

LikeLiked by 1 person